An article by Ukrainian Institute London’s Director Olesya Khromeychuk published by Atlantic Council, 29 Oct 2020.

AUTHOR

Olesya Khromeychuk, Director of the Ukrainian Institute London and a historian of east-central Europe.

I have always been suspicious of sweeping historical narratives that attempt to explain the complex events of the past in simple black and white terms. They remind me of the sanitized histories taught in Soviet schools, where there was no room for uncomfortable questions or critical analysis.

The breakup of the Soviet Union shattered this rigid ideological control over the past, but it created a whole new set of problems. Since 1991, the dogmas and taboos of Soviet orthodoxy have been replaced by memory wars that continue to loom large over efforts to forge coherent national identities in newly independent countries throughout the post-Soviet world.

For the past three decades, rival interpretations of Ukraine’s experience during the Soviet and Tsarist eras have repeatedly been exploited for political gain. These often purposely polarized versions of the past have served as proxies in the fight for votes and have allowed various political groups to avoid focusing on the problems of the present.

Predictably, Ukraine’s contested history also played a central role in the information offensive that accompanied Russia’s 2014 invasion. To this day, competing historical narratives remain at the heart of the undeclared but ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War.

Ukraine’s contested history played a central role in the information offensive that accompanied Russia’s 2014 invasion.

The challenge of finding a unifying national narrative is not unique to modern Ukraine. From Brexit to the Black Lives Matter movement, countries around the world are currently struggling to strike the right balance between past and present. Nevertheless, Ukraine’s unwelcome status as a laboratory of Kremlin hybrid warfare lends the country’s experience a special significance that extends far beyond the borders of the former Soviet domains.

What role should history play as modern Ukraine seeks to forge an inclusive civic national identity that is capable of uniting rather than dividing the country? This was the topic of a recent discussion organized by the Ukrainian Institute London.

Countering fakes with facts is not enough, argued leading information warfare analyst Peter Pomerantsev, who currently serves as director of the Arena Research Initiative based at the LSE Institute of Global Affairs and Johns Hopkins University.

Pomerantsev has published a number of award-winning books since 2014 exploring the Putin regime’s use of weaponized information and the Kremlin’s hybrid war against Ukraine. He was one of the people behind a recently published report entitled “From Memory Wars to a Common Future: Overcoming Polarisation in Ukraine.”

The study recognises the complexity of Ukrainian history and stresses that “debunking manipulations of history is of course important, but if it is the only strategy, it also risks repeating and reinforcing the agenda and framing set by the Kremlin.” In order to break out of this vicious cycle, the report advises, it is necessary “to foster a more constructive discourse around history that brings Ukrainians into a common national conversation.”

The success of any future discourse depends heavily on the ability of Ukrainians to identify common ground. Maria Montague, who served as a researcher on the Memory Wars report, explained that various themes uniting Ukrainians were evident during focus groups conducted in different parts of the country. These included the traumas and economic hardships of the 1990s, the Soviet Union’s Afghan War, and the 1986 Chornobyl disaster. Participants across Ukraine also shared negative attitudes towards corruption and a common sense of resilience.

Interestingly, attitudes towards these shared experiences were similar among Ukrainians, regardless of their geographical location. This directly challenges traditional representations of Ukraine in the international media, which tend to depict the country as hopelessly divided into a pro-Russian east and pro-European west.

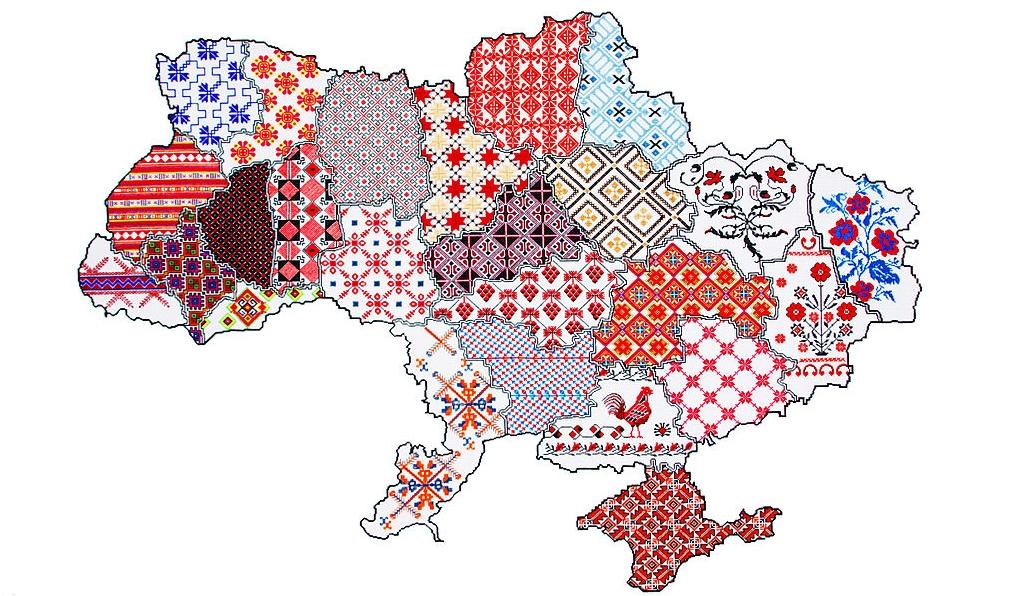

Anna Chebotariova, a sociologist and coordinator of the Ukrainian Regionalism Research Platform at the University of St Gallen, believes the reality on the ground is far less straightforward. “When you go to the level of Ukrainian oblasts, the picture is much more kaleidoscopic. In all regions of Ukraine, there is a very strong local identity,” she notes.

During the recent discussion, audience member and journalist Yuri Bender shared an anecdote that underlined the dangers of attempting to simplify Ukraine’s complex and multi-layered identity politics. He recalled how he had recently spoken with a group of young men from eastern Ukraine who identified as supporters of the so-called Luhansk People’s Republic and had spent their holidays in Crimea. While relaxing in a bar one evening, they had begun to cheer for Ukraine’s national football team. This upset some local ethnic Russian customers, who turned the TV off. A fight between the two groups ensued.

National identity in Ukraine often defies easy definition along ethnic, linguistic, or ideological lines.

This episode is a reminder that national identity in Ukraine often defies easy definition along ethnic, linguistic, or ideological lines. Here we see a group of Russian-speakers who welcomed the Kremlin’s “Russian Spring” in eastern Ukraine coming to blows over issues of identity with an ostensibly like-minded group who had backed the Russian seizure of Crimea. There are two obvious conclusions: Ukraine’s regional identities are far more nuanced than many observers appreciate, and it is inadvisable to generalize about the identity politics of Ukrainian society’s “pro-Russian” contingent.

The key message from the recent discussion on Ukrainian national identity was the importance of focusing on historical themes that have the potential to unite Ukrainians.

While it is convenient to blame Russia for exploiting divisions in today’s Ukraine, the fact remains that there are profound differences within modern Ukrainian society stemming from historical experience. Ukrainians must be encouraged to address painful issues in ways that respect rather than deny or dispute these differences.

The most problematic issues relate to the Second World War in Ukraine. While attitudes towards the Nazi occupation are overwhelmingly negative, opinion is significantly more divided on the role of the Red Army, with western Ukrainians in particular inclined to dwell on the brutality of the Soviet regime. At the same time, the idealization of the WWII-era nationalist movement in western Ukraine often alienates audiences in other parts of the country.

How should Ukraine approach these hugely emotive topics?

If Ukrainians are unable to discuss WWII without reducing the debate to the level of partisan confrontation, how can they expect to enter into a constructive dialogue over the ongoing war in the east of the country?

If Ukrainian society chooses to avoid discussing WWII, the debate will continue to be dominated by the Kremlin. This will have implications for the current conflict. If Ukrainians are unable to discuss WWII without reducing the debate to the level of partisan confrontation, how can they expect to enter into a constructive dialogue over the ongoing war in the east of the country?

The Memory Wars report suggests the need for a human-centric approach to sensitive topics from the past. Research has found that nuanced personal experiences can help facilitate meaningful discussion, with people who are otherwise reluctant to recognize the validity of competing narratives becoming more prepared to engage in complex debate.

This is vital. As a researcher, I have learned much about Ukrainian WWII nationalism from people whose views I do not share, but who are able to hold a discussion in which there is space for both speaking and listening. I learned about the Volyn massacre from someone whose family had suffered during these WWII-era events. Rather than chastising Ukrainians, she was interested in fostering debate.

At present, I cannot yet imagine listening to a separatist or a Russian soldier who had fought in eastern Ukraine. The wounds of the conflict are still too raw. But I would like to think that learning to address our complex past can also equip us to accept the painful present.

Ironically, Russian attempts to divide Ukrainians along historical lines appear to have backfired. Over the past six years, Ukrainians from all backgrounds have come together like never before to defend the country in a war that was supposedly rooted in their irreconcilable differences.

Ironically, Russian attempts to divide Ukrainians along historical lines appear to have backfired. Over the past six years, Ukrainians from all backgrounds have come together like never before to defend the country in a war that was supposedly rooted in their irreconcilable differences.

This offers hope for the future, but the national identity debate is still far from finished. Until Ukrainians can foster a constructive dialogue between those who differ over the country’s troubled past, Ukraine will remain hostage to memory wars that benefit nobody but the Kremlin.

This article was published by Atlantic Council, 29 Oct 2020.