Igor and Peter Pomerantsev discussed Ukraine’s multi-layered identity and national consciousness in a talk at the Ukrainian Institute London.

AUTHOR

Lesia Scholey, Ukrainian Institute London.

How do you solve a puzzle like Ukraine? How do you catch a cloud and pin it down? You come to the Ukrainian Institute London and catch great minds at work!

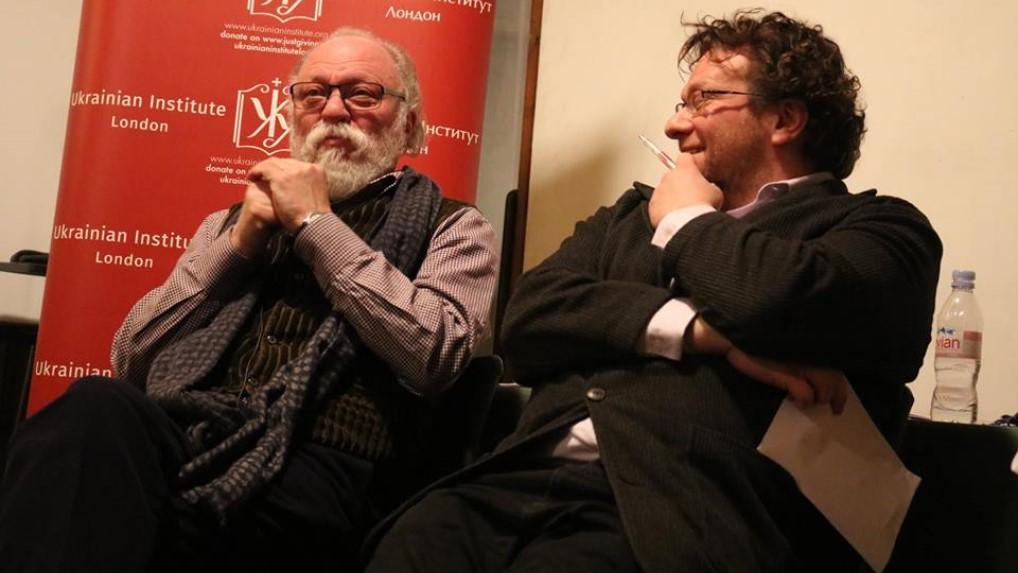

Yesterday evening at the Ukrainian Institute London in Holland Park, London, Ukrainian poet and Soviet dissident Igor Pomerantsev and his son Peter, author of the award-winning socio-political reflection and personal memoir Nothing is True and Everything is Possible, took to the stage to try and piece together Ukraine’s identity.

The chaos being experienced in Ukraine now, whether politically or culturally, is very much a part of what makes it a vibrant and free nation.

With a bit of Austrian, Hungarian and other national consciousness thrown in, it was a night where ideas and stories flowed freely, and where out of disparate threads emerged several interwoven themes. History is profoundly important in determining identity, so one must dig deep from the present into the past in order to understand identity. But equally, starting afresh is also necessary – the freedom to challenge received notions, the ability to move forward to new ideas of self – because identity is not stagnant and history continues to be written. The chaos being experienced in Ukraine now, whether politically or culturally, is very much a part of what makes it a vibrant and free nation. And now, as ever, Ukraine is in the process of forging its identity for the future.

Talking about his childhood and student and working days in Soviet-era Chernovets (Chernivtsi) and using it as a microcosm for Ukraine, Igor painted a vivid picture of life in a city that has always been not only Ukrainian but an ‘acoustic palimpsest’ – an audible layering – of many languages and cultures. Populated throughout history by a melange of Greeks and then Balkans, later Austro-Hungarians and Germans, as well as Jews and Romanians and Poles, Chernivtsi today and its inhabitants (present-day Ukrainians) can only truly understand themselves if they recognise the various influences that made up and still inform the place where they live. Similarly, foreigners need to understand these influences if they want to make sense of what constitutes the pieces and totality of modern-day Ukraine.

Restoration of cultural memory – the rehabilitation of names and texts, as well as identifying the unique landscape of architecture (bourgeois and modern) that gave life to the city and continues to shape the lives of its residents – is key to comprehending what a Chernivtsi Ukrainian is. As an example, Chernivtsi was possibly the only city in the USSR where streets were named after German writers Goethe and Schiller, Igor noted, and this had and must still have a profound impact on how people understand their cultural links and ultimately understand themselves – as some kind of Europeans.

Just as identity is formed by one’s personal beliefs and experiences, Igor said, it also depends on external perceptions – how others see and react to us.

Just as identity is formed by one’s personal beliefs and experiences, Igor said, it also depends on external perceptions – how others see and react to us. As an example, the famous astronomer Copernicus is now identified as Polish, but he would be very surprised by such a label since he was of mixed German and Polish heritage, worked and wrote in German and Latin, and the concept of nationality was not then what it is now. Identity therefore depends on one’s time and place in history, as well as how others place you. Identifying oneself as a Ukrainian these days – even if you write in Russian (as Igor does) – is a kind of ‘moral choice’ and a political statement. To identify oneself as Ukrainian is in some ways tantamount to saying one is in opposition to the war launched by Russia. But equally, Igor joked, he is happy to call himself the last ‘Austro-Hungarian writing in Russian.’

Ukraine’s current fight for survival, sharpened by the war imposed by Russia in the east of the country, has undoubtedly led to a cultural revival and strengthened Ukraine’s vision of itself as different from Russia. Peter noted that while Russians hold fast to the tradition of authoritarianism and empire, Ukraine is quite ‘horizontal’ (as highlighted by a recent sociological study). People derive their sense of who they are from their families, church and even local mafia. This puts them at odds with a country like Russia – imperial, ruled top-down – but these traits also importantly distinguish Ukrainians from their European neighbours, the Poles, who are far more institutionally-driven, according to Peter. In fact, father and son agreed, one can probably understand Ukrainian identity best if one acknowledges it as a fluid and chaotic thing, and much closer in spirit to places like Sicily or southern Mediterranean nations like Italy, where social ties and expectations are more similar and horizontal, than the East European countries to which Ukraine is usually compared.

Photo: The audience at the Ukrainian Institute London listen to Igor and Peter Pomerantsev.

Ukraine remains profoundly idealistic, and it has the advantage of a tabula rasa, or clean slate, whereas other countries like Russia or Poland must grapple with centuries of political traditions, expectations and formulated identities.

In the political arena, there isn’t much positive to say and Ukraine is as chaotic and besieged as it always has been: trapped between bigger powers and forces, at mercy to its own disunity and infighting. But as Igor noted, Ukraine also has little to none of the baggage that other nations carry in terms of what kind of state or nation it must be, or what form that must take. In that sense, Ukraine remains profoundly idealistic, and it has the advantage of a tabula rasa, or clean slate, whereas other countries like Russia or Poland must grapple with centuries of political traditions, expectations and formulated identities which they cannot easily shake.

Even with the war, Ukrainian literature is managing to move beyond the traditional ‘besieged’ mentality of previous writing, and this should give hope for exciting changes to Ukrainian identity in the future.

In the cultural arena, Ukraine also remains free, and as in politics, this freedom means embracing chaos. Its current cultural re-awakening – in an era following 20-plus years of independence and renewed Russian aggression – has led to a host of new and exciting literature, in both form and style. Even with the war, Ukrainian literature is managing to move beyond the traditional ‘besieged’ mentality of previous writing, and this should give hope for exciting changes to Ukrainian identity in the future.

While most of the population may remain passive and/or simply trying to survive, trying to find the ‘roof’ that will bring much-wanted security (and it remains an open-ended tug-of-war between Russia and Europe, NATO and the old empire, as to where Ukrainians will ultimately feel they can find that security), in culture, however, Ukrainian identity thrives. It is in a fluid process a lot like fermentation, with its destiny yet to be written, a fine wine that is yet to be produced.