How can literature help us to comprehend the tragedy of the Babyn Yar?

AUTHOR

James Bolton-Jones, MA student at UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies.

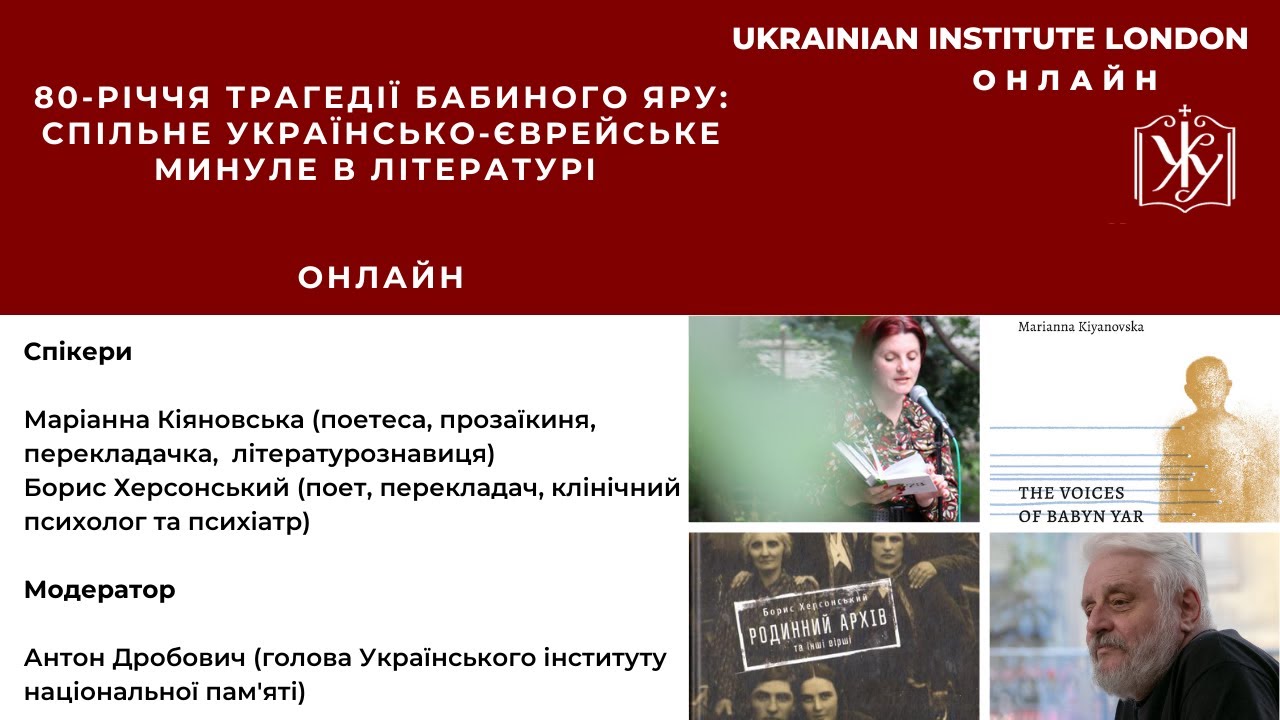

80 years ago, at Babyn Yar in Kyiv (‘yar’ means ravine), the Nazis murdered over 33,000 Jews. Overall, around 100,000 people – Jews, Ukrainians, Roma, and others – were murdered at the site in 1941. At this moving event on 30 September 2021 co-organised by the Ukrainian Institute London and Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter, leading Ukrainian poets Marianna Kiyanovska and Borys Khersonskyi discussed literary representations of the massacre. The discussion was moderated by Anton Drobovych, head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, who has curated educational programs at the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Centre.

Memory suppressed

The memory of Babyn Yar was suppressed by the Soviet authorities. As Khersonskyi explained, the Soviet leadership in 1947 launched its own anti-Semitic campaign, with Jewish cultural figures persecuted, arrested, and killed. With the details of what happened at Babyn Yar dismissed as Zionist propaganda, no efforts were made to memorialise the massacre, prompting Soviet-Russian poet Evegeny Yevtushenko, in his famous 1961 poem ‘Babii Yar’, to write: ‘No monument stands over Babi Yar’. Texts had been written about Babyn Yar before Yevtushenko, including in Yiddish, but these poets and authors never saw their work in print, said Kiyanovska, adding that their children and grandchildren preserved their work for future generations.

Comprehending the tragedy

Paraphrasing the Soviet-Jewish writer Vasily Grossman in his essay ‘Ukraine without Jews’ – one of the first accounts to detail the Holocaust – Drobovych remarked upon the strangeness of people, who teach themselves to feel nothing in the face of mass killings, but lose sleep over seeing a child knocked down by a car. To comprehend the scale of the tragedy at Babyn Yar, said Khersonskyi, you cannot just look at the statistics, because the number of people who died is beyond imaginable. You can only understand it through your compassion for individual people – to truly comprehend what happened at Babyn Yar, we must think about the individual tragedies.

A tragedy of this scale can only be imagined and understood through the fates of individual people who perished in it.

Borys Khersonskyi

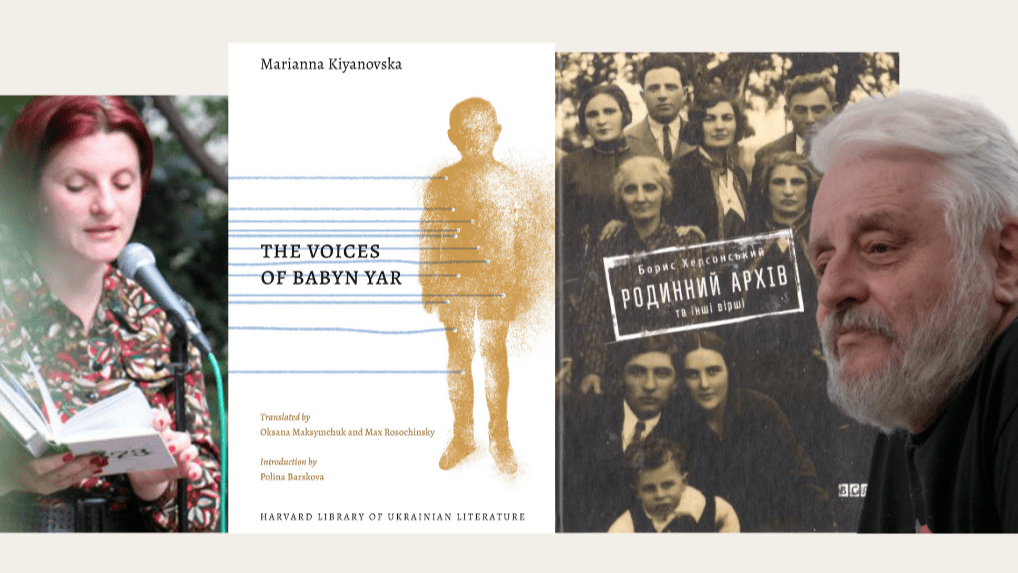

Kiyanovska agreed, noting that when researching her book of poetry – The Voices of Babyn Yar – she understood that the Holocaust is not about the statistics – horrific though they are – but about the specific people who perished. She noted too that across Ukraine there were many more mass murders during the Holocaust – in her own city in Western Ukraine around 16,000 people were killed. While there may now be a monument at Babyn Yar, other sites remain unmarked, the identities of those who died unknown.

Developing a culture of grief

It is the role of artists, composers, writers, and poets to contribute to and create a more open culture of grief.

Marianna Kiyanovska

Gaining a fuller understanding of what happened at Babyn Yar can help Ukraine develop a culture of grief, which at the moment is not developed, thought Kiyanovska. This deficit means terrible events, not just Babyn Yar, but also others like the Volyn massacre during the Second World War, the Chernobyl nuclear catastrophe, or the ongoing struggle against Russian aggression in the Donbas, have not yet been discussed openly or sincerely.

A Jewish or Ukrainian tragedy?

Drobovych asked if the two poets agreed with film-maker Sergei Loznitsa’s assertion that Babyn Yar is a tragedy only for Jewish people, not Ukrainians. Neither did. Khersonskyi emphasised a civic view of the Ukrainian nation – since Jewish people are an integral part of this nation, the Babyn Yar massacre was a huge loss to Ukraine, yet also a universal tragedy for humankind. Likewise, Kiyanovska reflected on the interlinked nature of the world – just as forest fires in the Amazon cause climate change affecting all of humanity, tragedies like Babyn Yar resonate far beyond its immediate victims. Every Kyivan lost a relative or a neighbour, Kiyanovska noted, and every city and town had its own Babyn Yar – the tragedy affected every Ukrainian. Khersonskyi acknowledged that historical relations between Ukrainians and Jews have been fraught, from the pogroms in the time of Bohdan Khmel’nyts’kyi to anti-Semitic lines in Shevchenko’s poetry, yet a complete understanding of Babyn Yar will only be possible when ethnic Ukrainians and Jews believe themselves to be part of a shared Ukrainian nation.

The discussion was followed by moving readings from both poets, translated by Nina Kossman, Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky.

Recordings of this event are now available on our YouTube channel. Immediately below you can find the event in Ukrainian and below this is a recording of the event translated into English.