Interview with Tamara Horikha Zernya about her award-winning novel Dotsya.

INTERVIEW

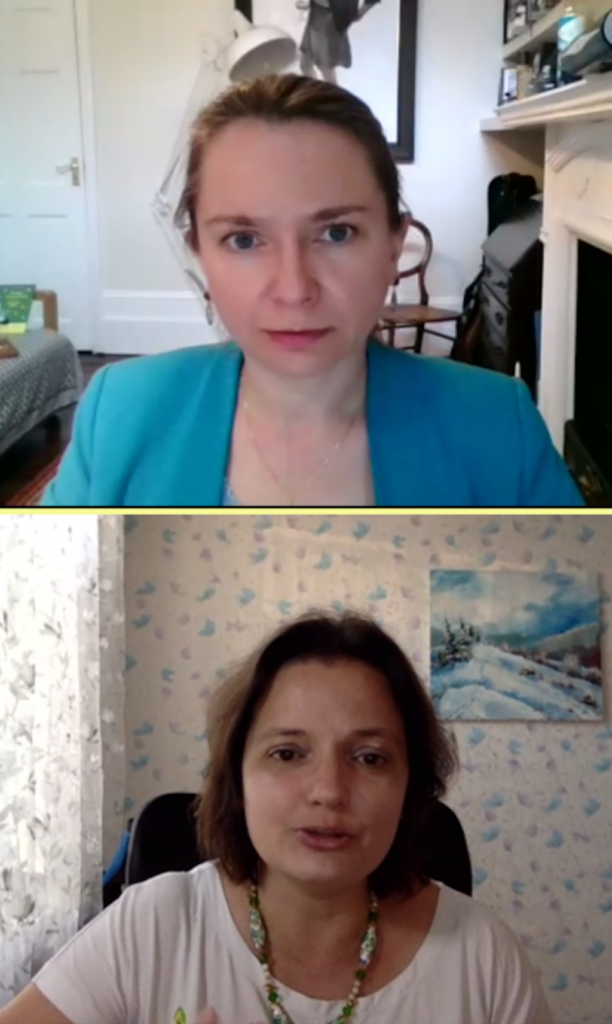

Tamara Horikha Zernya in conversation with Svitlana Pyrkalo, Trustee of Ukrainian Institute London and EBRD cultural advisor.

Write-up by Iryna Kupchynska and James Bolton-Jones

At the Ukrainian Institute London’s recent online event, author Tamara Horikha Zernya reflected on how she turned her experiences as a volunteer helping soldiers on the frontline into a novel, Dotsya (Daughter).

The novel was named the BBC Ukrainian Book of the Year in 2019. Marta Shokalo, the coordinator of the award, highlighted how remarkable this result was, since Dotsya is Tamara’s debut novel. In conversation with Svitlana Pyrkalo, co-founder of the award and trustee of Ukrainian Institute London, Tamara recounted tales about both her own life and her acclaimed novel.

On the road

Svitlana: Tamara, this book is about the war in Donbas and you know about it not from the media, but from your personal experience as a volunteer. You are a journalist, but you have lived through this war not only in this role, but also in one similar to that of your heroine.

Tamara: In the period before the war, I was a translator, a typical member of the middle class. I was a person who lived a normal and comfortable life. Then the war started, and like many people, I didn’t understand outright that it was a war, I was a bit slow on the uptake.

I understood that those events were extremely serious in very early June or even at the end of May 2014. There had been the events on the Maidan and then the annexation of Crimea, and what the government called an ‘anti-terrorist operation’ in Donbas. We saw that it was absurd and thought that it would end very soon: not more than a couple of weeks and the country would get back to normal. We had presidential elections, we managed to overcome the economic crisis, but on the other hand, we had a whole stream of internally displaced people who migrated to new places and didn’t know where to live. There were a lot of wounded soldiers in military hospitals and even civilian hospitals were packed.

We went to those hospitals to meet with those suffering and it was there that I saw that it wasn’t a terrorist attack, but a true war, even though it seemed most illogical. We read a lot about terrorism about extremism in the newspapers, but we were totally unprepared for the war.

Suddenly, I found myself on the road going to the frontline. That was when I met my husband-to-be. We were in a car with no back seats as we had taken them out in order to make more room in the car to pack various supplies, weapons, munitions and clothing for the people at the frontline. We were driving on totally broken roads and I was holding a grenade in my hand because I knew that if we were stopped by the separatists, it would be a simple way to end our lives and not get captured.

That was the moment when I understood that it was a totally different life from the peaceful one that I had got used to, that resembled a middle class life in any European country. We found ourselves in the grey zone under fire, knowing that if we made a wrong turn then we could lose our lives. So that personal transformation occurred in my real life and I had to somehow express it on the pages of the book.

Voices from the Donbas

Tamara: Many people from the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, volunteers, were strong patriots. A lot of help was coming from Donetsk when it wasn’t yet occupied: information and physical help – getting people in and out, food, water, everything was given by people from Donetsk. There was a big group of volunteers, undercover, guerilla – call them whatever you like, who helped and are still helping the Ukrainian army.

Svitlana: What happened to them?

Tamara: Various things. Some went away, some are still there, some are waiting for Donetsk to return to Ukraine, some are undercover. Every year in occupied Donetsk there are even public displays of Ukrainian support: the Ukrainian anthem at Independence Day, Ukrainian flags, patriotic graffiti, postcards. Thanks to the people from Donetsk, the occupied territory is not closed to Ukraine and its army and special services. And it is thanks to those people who at the very beginning volunteered in favour of Ukraine. I can think of a lot of people who perished as a result of their Ukrainian patriotism.

So Dotsya is an emotionally-charged book, it’s not an easy read because it shows what people are truly like. In such a critical situation a lot of that which is hidden was exposed; many people found things that they never thought they had in their heart: like courage, bravery, and determination. The book is about this moment. About people, their dramas, the tragic and the comic intertwined, mixed even with black humour. This is a book about the war, but it would never sell well and readers would never pay attention to it if it was exclusively about the war. Even in Ukraine, or particularly in Ukraine, where this topic is traumatic. People want to read about human stories, people and their conflicts, struggles, heroism, hesitation, anger, anguish, love and life.

Women and war

Svitlana: When discussing the war and its consequences you powerfully describe the implications for women first and foremost. Why was this important for you?

Tamara: I believe in sisterhood. I believe in women’s solidarity. Not in an abstract, theoretical solidarity, but a very practical one as I saw it in real life.

I know that when a woman gets into a situation of domestic violence, of abuse, she seeks support from other women and other women help her.

When we found ourselves in this national situation of abuse and violence, first of all we, women, started establishing links and connections throughout Ukraine. On online forums, for example, travel enthusiasts, mothers, those who cook or embroider, all kinds of different forums, women started to speak not about the hobbies but about how to provide support to the Armed Forces. I met a lot of volunteers-to-be on sites where you can share clothes or buy clothes from one another. And then we learn what it means to be a women-soldier, women-doctor or a nurse in Ukraine, what it means to be a mother or the widow of a soldier or have someone wounded. We quickly understood each other’s needs and helped each other.

The volunteer movement was a movement of women first and foremost, young, mature and even older women. Two thirds of the volunteers who supported the Armed Forces in my notebook were very different women but it turned out that we can literally save other women and their beloved. We shared clothes, foodstuffs, information, we helped the wounded, we nursed in hospitals. Now that the very hot stage of the war has subsided, we have still kept this very broad network of women’s support.

What matters is how, not how long, you live

Svitlana: Actually, a lot of women, and men for that matter, died in this book. I won’t give any spoilers explain how the book ends – but I want to ask, do you think the ending is optimistic or pessimistic?

Tamara: You know, I would have been much happier had I not seen a lot of the scenes that I witnessed in life on the front line and in the grey zone. I will tell you that actually what matters is not how long you live but the quality of life. Not for how long you’ll live, but how you eventually die. And there are certain situations that do not depend on us and the only thing we can do is to try to accept the situation with dignity. Save those who can be saved, remember those who couldn’t be saved and make sure everyone knows about them and remembers them. I hope that all of this suffering was not in vain. We don’t always know why things happen as they do but we should accept and go on living.